Myth Debunking in Social Studies Classroom

The Confederate flag controversy. Greece. Mass shootings. ISIS. It is difficult as a Social Studies teacher to keep up with current events. Sometimes, it is even more difficult to guide students in sorting out the interpretations of those events used by politicians, news outlets, and social media. Those interpretations are very often rooted in an “imagined” past which is not supported by documentary evidence.

Grumble as we may about legislation, administrators, and new teacher regulations,

it is a great time to be a Social Studies teacher. Never before have students and teachers had such instant access to information, never before have we been able to communicate and engage with humanity on such a massive scale.

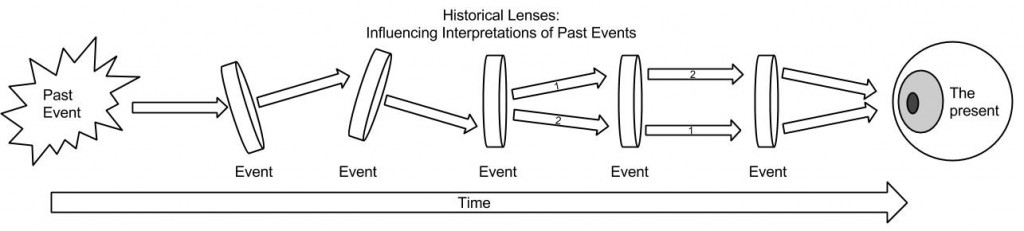

This new connectivity pushes us as educators toward a now visibly reachable goal – a more responsible consumption and interpretation of the human present and past. In the Social Studies past, students and teachers often regarded history in particular as a constant narrative. Because our and our students’ knowledge of history was based on very few sources – a textbook, a local newspaper, one of three possible television network news shows (I’m dating myself here) – it is understandable why history would seem to be a story already written. In my early days as a Social Studies teacher, I felt accomplished when I finally knew the “story” of the history I was teaching.

We were perpetuating myths. We allowed the textbook publishers to freeze history in a single moment. Some of us (including me at times) accepted it because we didn’t want to learn new “versions” of history.

We pay a price for this.

We struggle with diversity. We are unable to accept responsibility for environmental change. We fail to fix the human conditions that lead to religious extremism. We translate present challenges into the terms of our old textbooks: Putin and Russia represent a new Cold War, we see Islamic extremism and terrorism as monolithic, we accept the symbols of the Confederacy as reflections of the honor of their cause.

But these myths can’t stand for long. The sources and data behind them are becoming easier to find (or to discover as missing).

We as educators only need to have a more solid understanding of the sources of myth in the past, the evil effects of logical fallacies, and a reexamination of the historian’s toolbox.

That is the purpose of my course for Eduspire, called Social Studies Mythbusting. Controversy is a great source of motivation for students in Social Studies classes. This course will guide participants through an examination of beliefs held by the general public (and even many Social Studies educators) regarding history, geography, sociology, and even genealogy. Will these myths be “busted” or “confirmed?” Join us to find out, and spread an appreciation of controversy to your classrooms.

We certainly can’t root out all of the myths in one course, but we can encourage our students to search for truth and take on the critical responsibilities of 21st century citizens.

Interested in finding out more?

Other Social Studies Eduspire courses I teach:

American History: Managing Complexity with Digital and Non-Digital Tools

Secondary sources that encourage the promotion of interpretive historical skills in our students and our society:

The Problem With History Classes: Single-perspective narratives do students a gross disservice. by Michael Conway at The Atlantic

Why do people believe myths about the Confederacy? Because our textbooks and monuments are wrong. by James W. Loewen at The Washington Post

Pop History: The Past in Last Year’s Media (podcast) by the American History Guys at Backstory